The people of Rutba, Iraq are famous for their hospitality. But can kindness survive three generations of war?

THE ROAD to Rutba is smooth just long enough for us to settle into our seats. Then the jarring bumps begin as the car’s tires climb in and out of airstrike craters, sections of road torn up by ISIS, or around blown up bridges.

For hours the pattern repeats, the passing landscape a desert expanse broken only by occasional random building or burned-out car.

If I close my eyes, I can imagine the travelers who’ve been crossing the desert on this same path for as long as humans have been here. Even with cars and cell phones, the expanse between the modern-day cities of Amman, Jordan to the west, and Baghdad to the east, is vast. How much more so when travelers walked these paths ages before?

Halfway between Amman, Jordan, and Baghdad, Iraq, in a remote corner of Iraq that juts into Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, there is a natural resting spot.

That place is called Rutba, and that’s where we’re headed.

For most of Rutba’s history, it was a place of welcome. For ancient travelers, this “wet spot” in the desert kept nomads and their animals alive. It was as if the earth itself was showing hospitality in providing an accessible source of water.

In the 1930s, Rutba became a stopover for a British airline (back when commercial aviation was still new), for transport companies shipping goods from Jordan to Baghdad, and for water companies capitalizing on the resource. It was a place of welcome in a brutally inhospitable environment.

With time, a town grew around these earliest commercial ventures. Businesses developed to serve travelers driving through or flying in.

Rutba grew, based on the idea of being hospitable to everyone who came through. That was its essence from the start.

But can a community built on hospitality hold onto its essence through decades of war?

Over the last eighty years, Rutba has seen a pattern of military occupation. In the 1940s, when Britain built an air base in this remote, strategic city, local forces loyal to Iraq fought against British occupation.

In 2003, during the invasion of Iraq, American forces took over Rutba. While the US government had a policy of doing benevolent projects in local communities to “win over the hearts and minds of Iraqis,” what happened on the ground was sometimes very different. Iraqi detainees and civilians in Rutba were abused, instilling a culture of fear.

The situation was summarized in a 2010 article by The Mennonite, interviewing a local man named Sa’ady:

“We’ve been traumatized by the invasion,” he said. One night he and his family were awakened by the explosion of a bomb blowing open his front door, a terrifying sound that had been heard many nights in Rutba. They felt the terror of heavily armed soldiers storming through the house in the middle of the night.

With quiet sadness but without malice he said, “It was painful for me to see soldiers pull down a cabinet filled with nice china I had bought for my wife on my travels. They destroyed everything for no other reason than to humiliate us. I kept silent because I was afraid of being handcuffed and tortured if I said anything. I will never get over that night. Our children have witnessed these things and will never forget.”

The last US camp remained open in Rutba until 2010. After seven years of military occupation, the town of Rutba should have had the chance to rest, to restore itself. But it never got the support it needed. Little help arrived from the central government, and basic services were poor.

The people of Rutba tell me they are the face of Iraq to three countries: Jordan, Syria, and Saudi Arabia. But too often, they feel that no one has their back. They feel utterly let down.

Into that pain, exhaustion, and frustration, ISIS arrived in 2014, just three-and-a-half years after US forces left.

To ISIS, it seemed Rutba was made just for them. The nearby border with Syria, which they also controlled, meant their fighters could come and go as they pleased, essentially superimposing their own caliphate borders over the internationally recognized borders.

Roads originally developed to ship goods through the desert and between countries now allowed ISIS to easily move soldiers, weapons, and supplies. And the merciless desert provided a natural, protective buffer.

Iraqi detainees and civilians in Rutba were abused, instilling a culture of fear.

ISIS remained in Rutba for two years before the city was liberated. It wasn’t a hard fight—ISIS fighters withdrew to nearby villages and melted into the desert. In fact, ISIS still rules the desert, especially at night. They are preparing, launching attacks against local communities, biding their time until they are called up by ISIS leaders to begin war again.

Just two days before we arrived in Rutba, ISIS attacked a checkpoint less than 10 miles from where we planned to distribute aid. If you were told that ISIS is gone—you were misled.

The whole desert area here is still a militarized zone. Permissions have to be obtained to cross the dozens of checkpoints along the highway. The war isn’t over here. Not yet.

Rutba didn’t suffer the same kind of devastation under ISIS as cities like Mosul, but the years of war and occupation have been economically crushing. The main highway through town still isn’t safe. Businesses that rely on international trade were destroyed. Infrastructure that provided water and electricity was destroyed.

And the residents of Rutba—they are tired. They are hungry. They need to feel like someone is in their corner.

Chapter 2: Sitting With Sheikhs

“We hope you see the reality—the real life of Rutba, and the real people of Rutba.”

THREE STANDING tables are lined up in the thin wedge of shade made by the house. The mid-April sun is already hot in Iraq’s western desert, so we’re grateful for the careful arrangement.

Platters piled high with poached sheep and vegetables on beds of rice take up most of the room at each table. The rest of the space is crowded with small, savory dishes—salads, homemade pickles, beans, and okra cooked in rich tomato sauce.

Our host, the local sheikh, stands nearby, attentive to anything we might need. When he sees I’m not eating any sheep, he steps close, pulls off bite-sized pieces of meat, and piles them on the platter in front of me. When he learns I’m vegetarian, he shifts to spooning beans and okra onto the platter any time my rice looks dry.

In tribal Iraq, the host always serves himself last. We, as guests, come to the table first—our team, our local partners, a collective of sheikhs from nearby communities. We are offered first choice of the delicious food that fills the table.

When we step away, full, we have hardly made a dent. Next, the soldiers come to the table—those who are protecting us from possible attack by the ISIS fighters hiding out in the desert.

When everyone has eaten, when everyone is full, the sheikh and his family eat.

This midday meal in the middle of the desert outside Rutba perfectly illustrates the hospitality here. It runs so deeply in the culture, three generations of war couldn’t wipe it out.

When we first arrived in Rutba, we gathered with government and community leaders to plan our distribution of food packs and hygiene kits, which you provided for this remote desert town.

While decades of war and occupation had not diminished Rutba’s hospitality, it has left many families here with little means of providing for themselves.

It is essential for local leaders to reach a consensus on which villages will receive food. Every leader wanted to help their own people, of course. There were a lot of heavy negotiations as they sorted out the needs their people face, and whose needs were most acute.

We went on to talk about the ongoing impact ISIS is having on the community—the attacks that still happen, and how the city continues to close its gates and final checkpoints at 4:30 pm, as night is when ISIS is most active and dangerous.

I shared with the leaders what I knew of Rutba’s reputation. I mentioned a story I’d heard which took place during the war with the US.

The only thing we could do to repay them is to tell the story of their hospitality.

Shane Claiborne

A group of American peacemakers—including Shane Claiborne from The Simple Way and Cliff Kindy from Christian Peacemaker Teams—were driving through the Iraqi desert when their car blew a tire and crashed. A car traveling the opposite direction stopped and took the men to Rutba, where they received emergency medical care at a makeshift clinic.

Just three days earlier, the US had bombed the hospital in Rutba. The group of Americans was so moved by the radical hospitality they received—what they experienced ran counter to the common stereotype of Iraqis and Muslims as evil terrorists.

“They… saved our lives,” Shane Claiborne wrote years later. “It is one of the most powerful experiences of my life. When we went to pay them for their services, they refused our money, and insisted that the only thing we could do to repay them is to tell the story of their hospitality, and of the bombing that destroyed their hospital.”

![]()

“ISIS was just an intruder to the body of Rutba,” the town director explains to me. He was anxious for us to know the community as he knows it.

“The community of Rutba rejects all the violence and the things that ISIS was doing. It’s a peaceful, open community here. It accepts all, from different communities, from different religions or different ethnicities. What happened is ISIS came, but the community itself rejected every single thing ISIS did.”

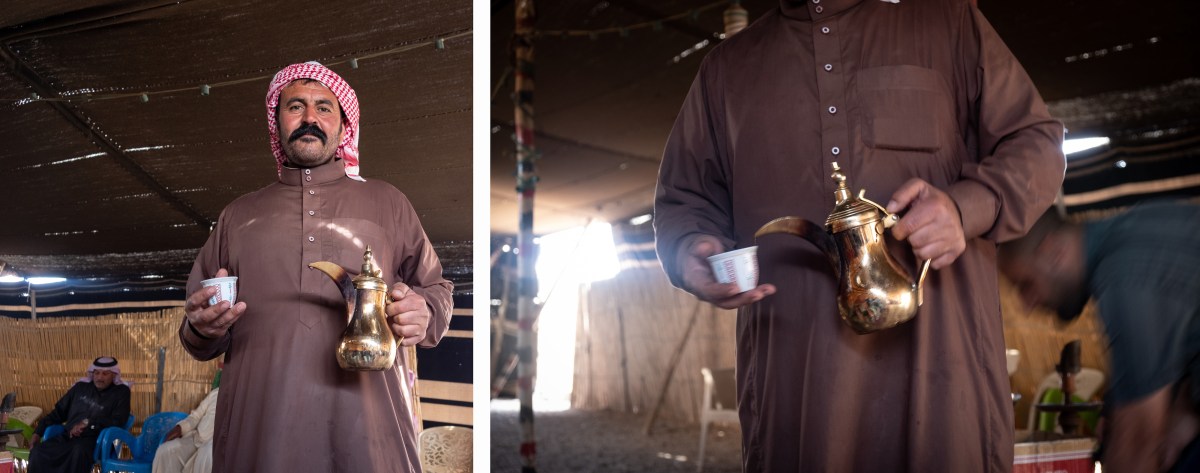

We ring the perimeter of the sheikh’s tent, grateful and satisfied after the generous lunch. Heat radiates off the hand-woven roof above our heads, causing beads of sweat to rise up on our foreheads.

Bottles of cool water are placed in front of each one gathered. Next come small glasses of hot, sweet tea. And last, hot coffee served to us one at a time from a beautiful, spouted pot. I hand back the empty cup, only to have it refilled.

When I down the second cup, I hand it back with the slight wiggle of the cup that indicates I’ve had enough, and the server moves on to my colleague beside me.

We don’t intend to be in this spot much longer, but with a few quick words, one of the men begins cutting the stitching that fastens the fabric roof to the walls behind us, allowing a cooling breeze to flow from the open door.

It is one of the countless kindnesses we experience in Rutba.

“We hope that you see the reality—the real life of Rutba, and the real people of Rutba. They are the same people that your folks saw before, when they came here. They are the same people. They didn’t change, and you will see this by yourself.”

To be honest, I was worried about what we would find in Rutba. I was concerned that years of violence and an economy devastated by war would change the people of this place—that it would harden their hearts. Instead, I found nothing but welcome.

The war with ISIS is far from over, here in the western desert. Iraq just held nationwide elections, with major policies hashed out between candidates on television news each night, and the world—believing ISIS to be utterly defeated—has already moved on.

The people of Rutba wonder once more if they will be forgotten, or if anyone will stand with them.

Chapter 3: Who Gets a Share?

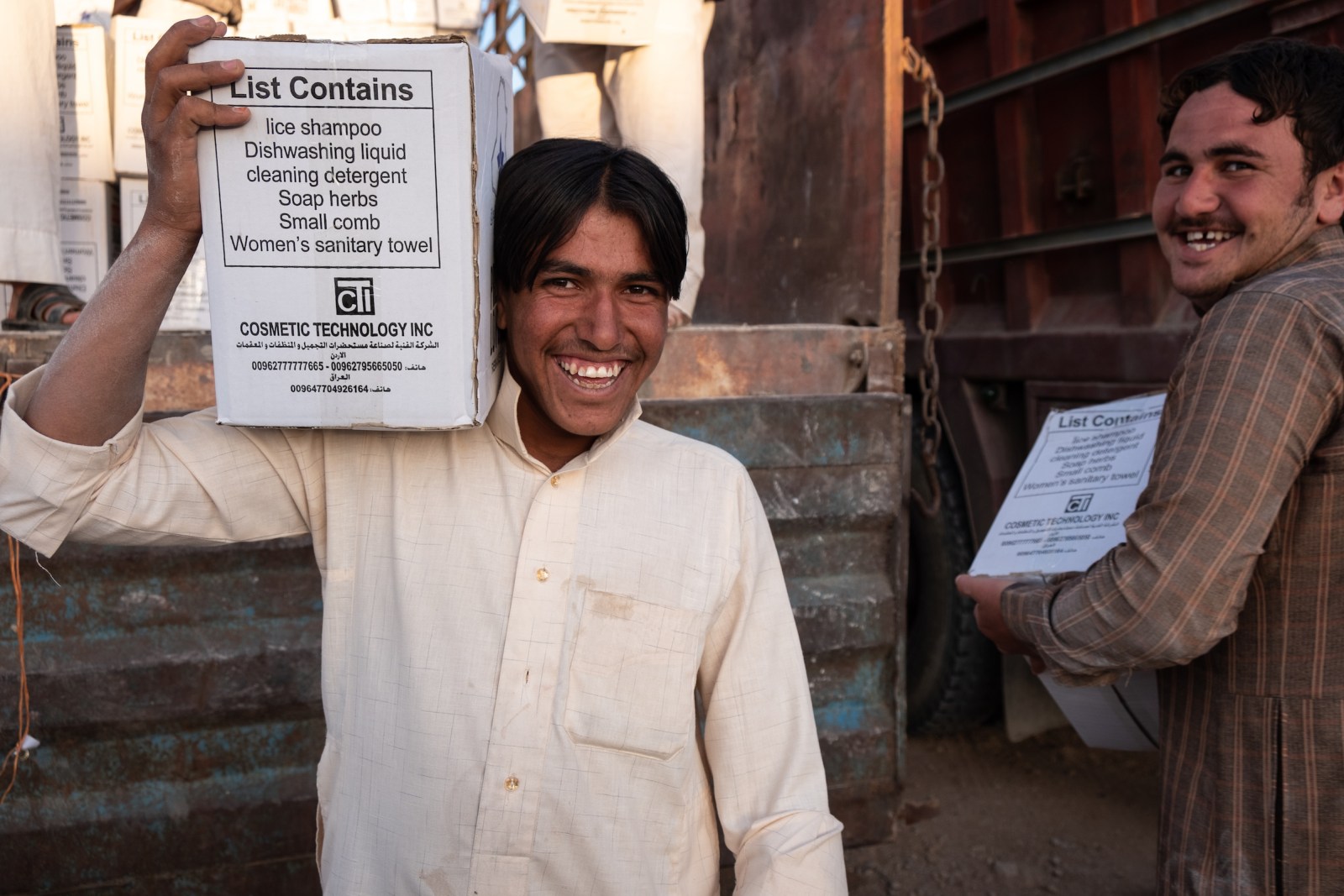

The trucks arrived in Rutba with food and hygiene kits. Now came the hard part: deciding who got a share.

ON DELIVERY DAYS, when the trucks roll into position for a relief distribution, filled with the food and hygiene kits you provide, the atmosphere is electric. So much work goes into preparing for this moment, and everyone is invested in the day going well.

Long before your aid arrives, our partners work with leaders in each community—each delivery neighborhood, even—to make preparations. Through a consensus of community leaders, locations are chosen, volunteers are recruited to help on the day of distribution, and security is put into place.

In remote towns like Rutba, still surrounded by ISIS fighters, arranging security is critical for the safety of those who come to receive food. Rutba is still considered a militarized zone, so a delivery like this requires permissions from multiple layers of government. It is a long process which requires patience.

Finally, there is the most difficult decisions to make: who will receive food?

Community leaders want to serve their people well. They want to represent their needs well. Through consensus, community leaders decide who is most in need, and make sure that those residents get food first.

When the trucks roll onto the site, families line up for a receipt that allows them to receive a “share.” They show identification that proves the size of their family, to make sure that large families get enough for every member. The receipts are marked as families move through and receive aid, to make sure that each family gets their share, but can’t step back into line for a second share.

So, who actually gets a share of aid?

Widows.

After delivering to remote villages outside Rutba, we set up a delivery site in the municipal yard at the center of town. As we approached the site early in the morning, a line of women—many of them widows—were lined up to the right of the entrance gate.

We stopped to talk with the women, and heard stories of just how tough it is for them to provide for their families. The first woman in the line—she was in line at 6am, determined to get a share of the food.

Orphaned children.

Hajer and Tabarek are two shy girls, whose uncle pushed forward to meet us. They live with their uncle, as they are orphaned and not old enough yet to marry.

Though Hajer and Tabarek live under their uncle’s roof, they got their own share of food. It is a small way that orphans can help the extended family that cares for them.

Those who work, and still can’t make ends meet.

Many of the women we met at the distribution were eager to talk to us. They wanted us to understand that they aren’t looking for charity, not looking for a handout—just a little compassion.

One woman described her life working full-time at the local hospital, and caring for her disabled husband and their eight children. They are displaced from a nearby town still too dangerous to return to. She earns a salary each month from her work at the hospital, but it is exactly enough to cover rent and not a penny more.

I ask how they eat. She pauses, tells us that sometimes neighbors invite them for meals, and then she gets quiet.

This month, she won’t have to worry how she will feed her family.

Those who can’t find work.

Three successive generations in Rutba have known war. Because the town was built around a single industry—the shipping of goods between Syria, Jordan and Baghdad—periods of violence cause the economic tides of the town to shift dramatically.

International shipping requires safety and security, good roads, and easy access. None of these elements have been present since ISIS appeared in Iraq’s western desert, and no one knows when safety and stability will return.

For now at least, they have something to help them through the uncertainty.

Local volunteers.

It takes strong backs to shift thousands of pounds of food and flour. Men from the community volunteer to help their neighbors get food, and in doing so, earn a share for themselves.

In Rutba, the same volunteers showed up for a second day of working in the sun, even knowing they would only receive one share. They showed up simply for the reward of helping their neighbors.

![]()

When you showed up in Rutba, you brought relief to villagers who still have to protect themselves from ISIS attacks every night. You honored the hospitality they so freely give to everyone by showing kindness and generosity of your own. You saw them for who they really are—despite generations of war.

You were present with Iraqis who often feel forgotten, despite the risk. And you stood with families who didn’t know how they would get by.

You see the people of Iraq for who they really are—extraordinary, resilient, hospitable. Stand with them as they rebuild their lives. Give today.

Vintage aerial photo of Rutba wells by American Colony , Photo Dept, 1932.