Why would anyone make a memorial to the lynchings that happened in America?

What good could come out of it?

How can bringing up such a painful part of our history be healing?

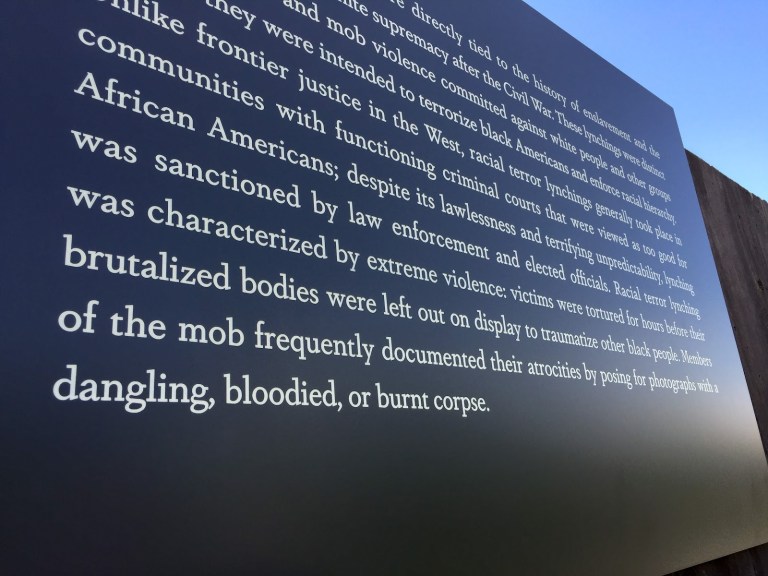

Last month, the first memorial of its type opened in Montgomery, Alabama: the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, honoring black Americans who lost their lives to the racial terror of lynching at the hands of white Americans.

If you’re wondering how a memorial like this helps, you’re not alone. In a recent story, some who live near the memorial expressed fear that it would open “old wounds,” that it would dwell too heavily on the past.

But not all “old wounds” are truly healed. The past, left undealt with, has a way of crippling the future.

Real peacemaking, real reconciliation begins with listening. With remembering. With acknowledging our shared story, including the parts we’d rather not remember. We’ve seen it over and over again in Iraq.

We’ve learned what people need first when violence erupts, when ISIS or some other group terrorizes people. And it’s not what you think. Even before food, before water—the first thing families need is someone who will listen to them.

Many of the wounds they’ve suffered are decades old—they aren’t just the scars of the most recent conflict. They’re still living with the fallout from Saddam’s use of chemical weapons 30 years ago. They’re still living with the aftershocks of decades of oppression, from within and without. It’s not the past for them. These injustices have generational effects. We cannot truly create a more beautiful world together if we ignore them.

The same is true for American veterans who served in the Iraq War. We know many still carry the effects of violence, even though the war is in the past for them. That’s why we continue to honor them. Every Veterans Day, we remember the past, not to open old wounds, but to honor and remind those who served they are not alone. We never forget—because when we pause to remember the past, we invest in healing our present. We honor the unseen pain. When we acknowledge individuals histories, we shape a new future alongside each other. Because we believe in unmaking violence and creating the more beautiful world together.

In over ten years living and working on the frontlines of conflict, we’ve learned that listening is the most powerful act of love. Listening is the first step in becoming whole, the first step in healing.

Locking eyes, pausing, and hearing someone’s story of pain can offer what’s needed most. To be seen. To be heard, to be reminded that they are human beings first. Though the violence tries to deny their humanity, we have the power to affirm it through the radical act of listening. Though the experience they talk about may feel like it’s in the past for us, bearing witness to their continued pain injects healing into today.

![]()

In a sleepy Minnesota town in 1920, three African-American men were lynched by a mob of thousands. They were left swinging from a downtown lightpost while locals crowded together to take photos that would become postcards sold in Duluth—my city.

Last month, I joined a delegation from Duluth to bear witness to the opening of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, because I’ve experienced firsthand the power of remembering as a way of healing broken communities.

In 2003, Duluth opened its own memorial to our city’s lynching victims—and it became a brave new beginning. A place for us to acknowledge the impact of racism and to express our commitment to another future. Standing on that hallowed ground empowers us to unmake the violence of racism by acknowledging the pain. It gives us a shared starting point, while propelling us toward The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible.

We recognize that this doesn’t change what has happened. But we can make positive change, one person at a time.

— family member of a lynching victim, who attended the memorial opening

Bearing witness to the grand opening of the memorial in Montgomery, with each of my sons sitting on either side of me, I was blinded by the hope I heard all around. As one of a minority of white people in attendance, and as the mom of a multicultural family, I expected to feel somber. I braced myself to feel like an outsider—or to feel shame. This history was never told to me by my family or in my schools.

But instead, the room buzzed with a truth, a sense of relief that this reality wasn’t being dismissed like spoiled milk, unwanted and pushed aside. Instead it was being honored. It was being seen. The families of those who were lynched were having their pain remembered instead of hidden. And in this historical moment of bearing witness to the stories and the pain of the living family members of lynching victims, healing made its way up and down the aisles, through the speakers, and sitting alongside of all of us in attendance.

It’s going to take generations to get us where need to go, but this is a great start.

— family member of a lynching victim, who attended the memorial opening

For the first time, I heard a resounding belief that the future could be better than our present. That reconciliation could begin because truth was being honored through this memorial. Listening to the experience of families of those who were lynched was a profound honor, rather than a reopening of “old wounds.” In the auditorium, my son leaned over with excitement and whispered, “Mom, I didn’t know there are so many people who care about the violence done to people with my color of skin!”

To love first and love anyway can be uncomfortable or even costly. But love never fails when it shows up.

As the crowd and the music carried us out into the Montgomery spring air, I knew one thing was true: listening isn’t the first way to love only in Iraq. Listening is how we love and heal in America, too.

Our country can become whole again as we hear each other. One memorial, one name remembered and honored at a time. We can shape our future by how we choose to listen to each other now.

At the opening of the memorial, Bryan Stevenson, the founder of The Equal Justice Initiative and one of the driving forces behind the memorial, said:

I believe we can do better in America. I do. I believe it. In our new America, we won’t have a criminal justice system that treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than poor and innocent. In our new America, we won’t have the highest rate of incarceration in the world. We won’t hate the poor in our new America. No one will be illegal in our new America. We won’t discard the disabled. Women and girls won’t be harassed or excluded. In our new America, there will be no presumption of dangerousness for black and brown people to live in fear of the police or judges.

Peace can happen. We can reshape our country’s future by remembering our past.

Love leans in, making a place for us to listen to our shared story. This is how we choose peace over self-protection, listening instead of fear.

Fear tells us truth is too risky or painful and that reconciliation isn’t possible. But do not believe it.

Reconciliation can happen when we choose to remember.